Karolina Ramqvist on the Images in The Bear Woman

We asked Karolina Ramqvist, author of The Bear Woman, translated by Saskia Vogel, to tell us about the images that play a such a large role in the book.

After I heard about the legend of Marguerite de la Rocque I soon became consumed with the subject of the French Renaissance, an era when a modern understanding of humanity started to take shape with new ideas of literature and art. I was a new mother of three, pushing my huge double buggy around the streets of Stockholm, staring at my iPhone, daydreaming, and trying to make sense of who Marguerite was, this young French noblewoman who could read and write and was left to die on an island in the north Atlantic after a sexual scandal aboard a French colonial ship.

I believe I wanted to escape my own time and in order to do that, or try to, I used a lot of images that I found on the internet. The first one I saw was a red chalk portrait of Jean-François de la Rocque de Roberval, the captain who marooned Marguerite, his young relative and confidant, outside of Newfoundland and Labrador. At the time I didn’t know of any pictures of her, so I kept googling for random paintings of young French noblewomen from the 1540s. I looked at portraits of the famous people around her: the French king François I who was Roberval’s friend and had appointed him viceroy of Canada; the king’s cartographer and explorer André Thevet who would write about Marguerite in his La Cosmographie Universelle; and the queen, and author, Marguerite de Navarre, who incorporated a version of Marguerite’s story in her famous story collection Heptameron. Both the royal siblings and Roberval were portrayed by court painter Jean Clouet.

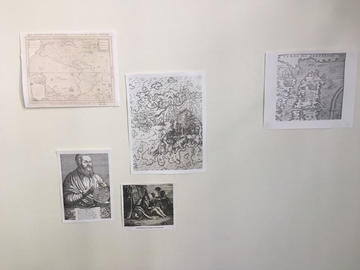

At my office in Stockholm, I put the images I had found on the wall by my desk. There was a black and white photo of Le Nouveau Monde Descouvert et Illustré de Nostre Temps (1), the map from 1575 by André Thevet that is in the maps collection of New York Public Library, in which Thevet had divided the New World into three territories, lieues Italiques, lieues Francoyza, lieues Marinza – Italian, French, and Spanish.

In American historian Elizabeth Boyer’s book, A Colony of One, from 1983, I found the anonymous etching of Marguerite on the island (2), which had originally appeared in André Thevet’s La Cosmographie Universelle, to illustrate his interview with Marguerite. At the time the marooning was of course a very delicate matter, but when Thevet’s work was published in 1575, Roberval and King François I were both dead. From what I read, I got the feeling Thevet was as obsessed with Europe’s colonial project as I was with Marguerite, and I figured he had met her at a point in his career when he needed to soak up anything he could find about the New World, since he himself hadn’t really been anywhere yet and had to rely on witnesses like her for his research. Pictured in the etching are lots of things that tell us about Marguerite and what happened to her on the island, all the hardships she had to endure, but there are also some confusing details, like the palm tree in the center of the island. Thevet took great interest in everything concerning the New World, but either he didn’t know a lot about palm trees, or he didn’t take time to instruct his engraver about the nature and weather conditions in this part of North America. I wondered who had made the drawing and wanted to know what thoughts he had on the subject. Did he too get to meet her and speak with her? Elizabeth Boyer suggests that Marguerite could have made the drawing herself, but in that case, I wonder, why would she have put the palm tree there?

(3) Îles-Saint-Marthe was the name Jacques Cartier had given to the archipelago that is now called Harrington Harbour, where Marguerite was marooned. When Jean François de la Rocque de Roberval put her on the island, he said it was inhabited by wild animals and ghosts and called it Île des Démons, presumably in order to prevent sailors and fishermen from going ashore to find her. Later, Jean-Alfonse de Saintonge, pilot of Roberval’s fleet, would rename it Île de la Demoiselle on his route, maybe as an homage to her. Isle of Demons appears on maps as early as 1506, in different locations, which was very confusing to me. It is nowadays considered a phantom island and is sometimes associated with Quirpon Island in Newfoundland and Labrador. Here it appears on Venetian cartographer Giacomo Gastaldi’s 1556 map, La Nueva Francia.

(4) An engraving by Swiss 18th century artist Sigmund Freudenberg, printed in an English 1894 edition of Heptameron and originally made for Les Nouvelles de Marguerite, Reine de Navarre 1780-81 with the caption, “The wife reading to her husband on the desert island”. As with everyone who depicted her in some way in their work, I wondered what went through Freudenberg’s mind when he made this piece. Did he think of her the way I did? Was he too obsessed? Maybe not. The hut looks bigger than I imagined it and very tidy and the palm trees are here again.

(5) A portrait of André Thevet from 1586 by engraver Thomas de Leu, printed in Thevet’s Grand Insulaire et Pilotage. The former Franciscan friar Thevet is pictured here, as always, with his cartographic tools, his globe and his divider, and with a caption describing him as the world’s number one explorer. Like his other books, the Grand Insulaire combines myth, fantasy, and facts in a way that I found inspiring, funny, and annoying. Thevet had high moral standards and such great ambitions for his understanding of the world and at the same time didn’t seem too occupied with accuracy in his writing. But most of all I fantasized of his meeting with Marguerite, of how he saw her and what his thoughts were when he decided to tell her story.